14 June 2009

New York Times

Source

Shanghai Journal

Gay Festival in China Pushes Official Boundaries

By Andrew jacobs

SHANGHAI — It was shortly after the “hot body” contest and just before a painted procession of Chinese opera singers took the stage that the police threatened to shut down China’s first gay pride festival. The authorities had already forced the cancellation of a play, a film screening and a social mixer, so when an irritated plainclothes officer arrived at the Saturday afternoon gala and flashed his badge, organizers feared the worst.

After some fraught negotiations, Hannah Miller, an American teacher who helped put together the weeklong festival, agreed to limit the crowds, keep the noise down and, most important, “not let anything happen that might embarrass the government,” she explained after returning from the impromptu sidewalk meeting. “That was a close call,” she said.

Crisis averted, the party continued.

And so it went for Shanghai Pride week, a delicately orchestrated series of private events that revealed how far China’s gay community had come, and how much further it had to go. In the 12 years since homosexuality was decriminalized in China, there has been an unmistakable blossoming of gay life, even if largely underground. Most big cities have gay bars, and social networking sites ease the isolation of those living in China’s rural hinterland. Antigay violence is virtually unheard of.

But official tolerance has its limits. Gay publications and plays are banned, gay Web sites are occasionally blocked and those who try to advocate for greater legal protections for lesbians and gay men sometimes face harassment from the police. For years, movie buffs in Beijing have tried, and failed, to get permission for a gay film festival.

This month, public security officials forced Wan Yanhai, a prominent advocate on gay issues, including AIDS, to leave Beijing for a week because they feared he might cause trouble during the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

“Sometimes I feel like we are playing a complicated game with the government,” Mr. Wan said. “No one knows where the line is, but we just keep pushing.”

The government, of course, can push back much harder. Last month, China issued a directive requiring that all new computers include filtering software to block pornographic images as well as Web sites with words like gay, lesbian and homosexuality. Mr. Wan and others fear the new rules could effectively ban online information from AIDS organizations or groups that help young people grapple with their sexual orientation.

To further confuse matters, China Daily, the official English-language newspaper, splashed a story about Shanghai Pride on its front page and ran an editorial lauding the event as a welcome sign of China’s social reformation. The progress did not extend to the country’s Chinese press, however, which made no mention of the weeklong festival.

During three months of planning, organizers had a rough idea of the limitations: no Chinese-language advertisements, no banners, no parades. Ms. Miller, 30, who helped start Shanghai’s first gay Internet mailing list in 2006, explained why the event’s main organizers were almost entirely not Chinese. “As a foreign passport holder, I think we’re less easily intimidated,” she said.

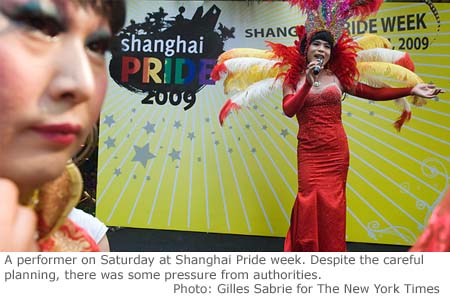

Despite the careful planning, there were some disappointments. Last week, the authorities showed up at several sites and warned their owners that there would be “serious consequences” if they held scheduled events. A staging of “The Laramie Project,” a play about the murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay college student, was canceled after the police interrupted a rehearsal to write down the names of the actors. As word of the crackdown spread, performers canceled their appearances and bar owners apologetically told Shanghai Pride to go elsewhere.

By Saturday, any lingering anxiety had seemingly evaporated as hundreds of people crammed into a bar to watch lip-synching divas and a silent auction to benefit AIDS orphans. At one table, a woman painted hearts and rainbows on the faces of Westerners and Chinese revelers.

The celebrants were self-assured, unapologetically gay and mostly under 30. There was Gu An, a 19-year-old economics student who shares a dorm room at Shanghai University with his high school sweetheart, and Wang Liang, a 27-year-old furniture designer who might have been the only person to bring his mother.

Jin Ying, 49, Mr. Wang’s mother, said she was a bit startled when he came out two years ago, but she was not entirely surprised. “I’m his mother, so I had my suspicions,” she said. “If he’s happy, I’m happy.”

But Mr. Wang’s mother was a rare exception. For most gay men and lesbians in China, revealing their sexuality to their families is unimaginable. Parents expect their sons and daughters to produce heirs, an obligation that has become even more intense in a society where single-child families are the standard.

Huang Jiankun’s joyous mood darkened when he recalled the pain his coming out brought to his parents. His father, a retired army officer, wept uncontrollably. His mother made him promise that he would stay away from men. Visits home during the Chinese New Year have become unbearable, especially when relatives pepper him with questions about why he is still unmarried at 30. “I can handle the pressure, but I can’t stand to see the pain on my parents’ faces,” said Mr. Huang, who works in public relations.

To assuage his parents, he orchestrated a fake wedding to a lesbian friend, but eventually the truth came out. “The problem is when you lie, it becomes connected to another lie and you can’t keep it up,” he said.

Just then, four couples took the stage, and an ordained minister pronounced them married, if only symbolically. “Being gay is great,” Mr. Huang said, his melancholy banished.

On the other side of town, as the young and the self-possessed celebrated their sexual orientation, a few hundred men, most in their 50s and 60s, packed into the Lai Lai, a grimy ballroom in one of Shanghai’s less glamorous neighborhoods. Three nights a week, the men slip away from their wives to dance with one another to the music of a warble-voiced singer.

As he led his clumsy partner across the dance floor, Zhou Aiwen, a 73-year-old retired cadre, spoke of a lifetime of unrequited desire but also of his commitment to Chinese tradition. “My son has a kid now, so I don’t have to worry about anything,” he said with satisfaction.

The subject of gay marriage came up, and Mr. Zhou laughed dismissively. “In China we need another 30 years before that can happen,” he said as the clock struck 9 and the dance hall abruptly emptied out.

0 Responses to “NYT: Gay festival in China pushes official boundaries”